Anthony Cudahy on Lily Wong

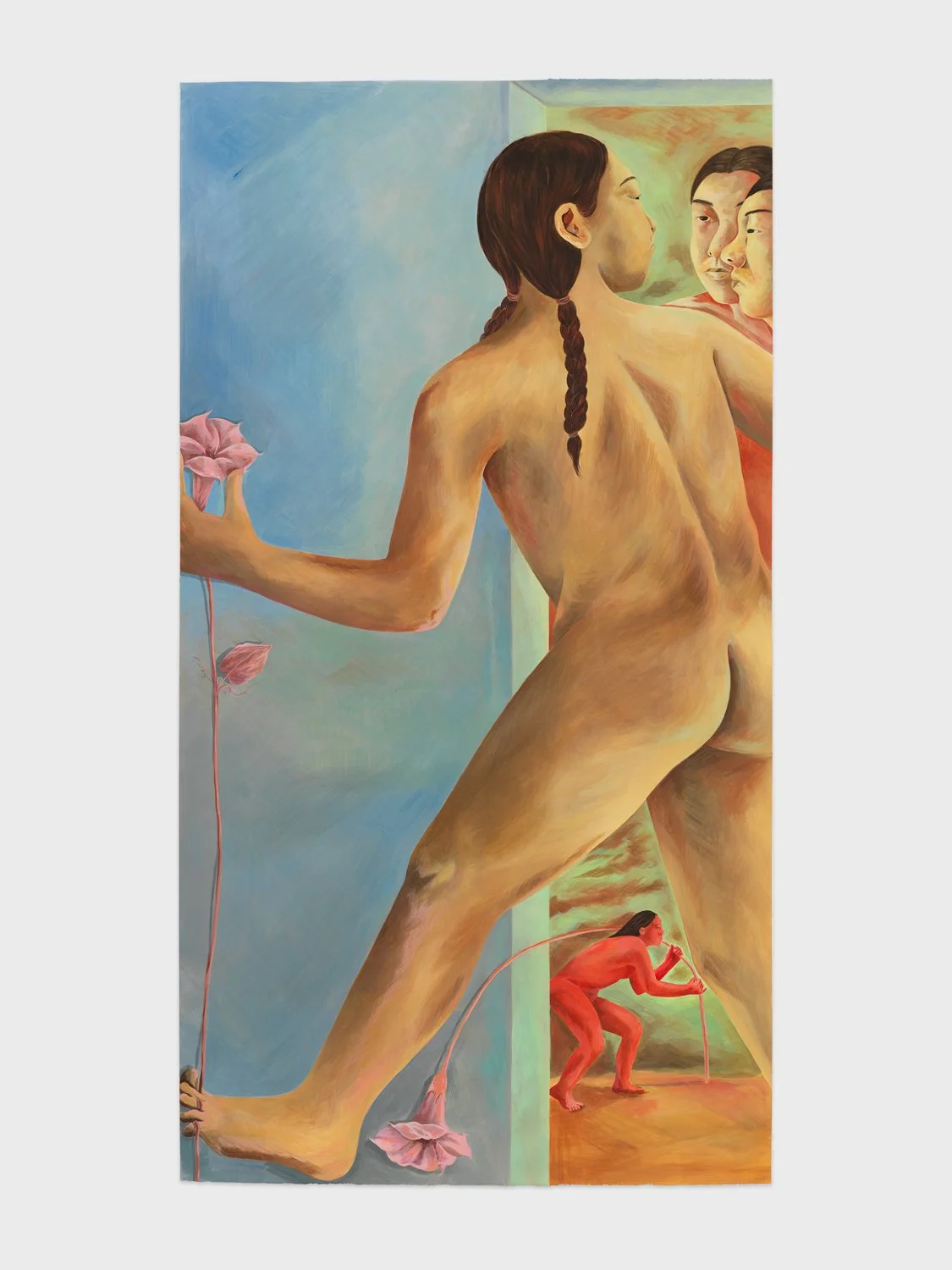

Lily Wong, Moonflower, 2025, acrylic on paper, 48.5 x 26 inches

Studio visit with Lily Wong on the eve of her current solo exhibition, Time, as a symptom, at Lyles & King

Precipice

Don’t lose your footing

The wall might be a floor

I type this list into my Notes app as I visit Lily Wong’s studio. In her work, she plays with the tenses and outlines of narrative. There is a flexibility here. A reliable narrator is not to be found. The older one gets in life, the less sure one is of their fixed personhood. How open can an artist leave their own story? One piece in particular, Moonflower, contends with all of this. The main figure is not simply mirrored but divided into three. Scale is thrown into question by the small (?) figure in the distance, holding the stem of a giant (?) flower, the bloom of which enters the room along with the main figure. Her foot is entangled in another stem, and she seems to be taking a step forward, but without solid grounding.

*

Wong’s studio is neat. Large sheets of paper are pinned to the walls and methodically layered over weeks and months with thin strokes of acrylic. Remnants of paint from wiping her brush on the surface or testing a color/mark surround the pieces like Seurat frames. These color relationships have become more complex than in previous works. Interconnected, surprising colors often cast reflections onto other portions of the paintings.

References abound:

A woodprint, Suzaku Gate Moon, from Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s 100 Aspects of the Moon; The Groping Hand, a small, oddball George Tooker; Bosch’s The Pedlar; stills from a Patty Chang performance video. Wong has kept these potent images taped to her studio wall for years, or in spreads ready to be poured over in her library of art books, allowing her to ruminate on them and let them seep into her work, transforming it.

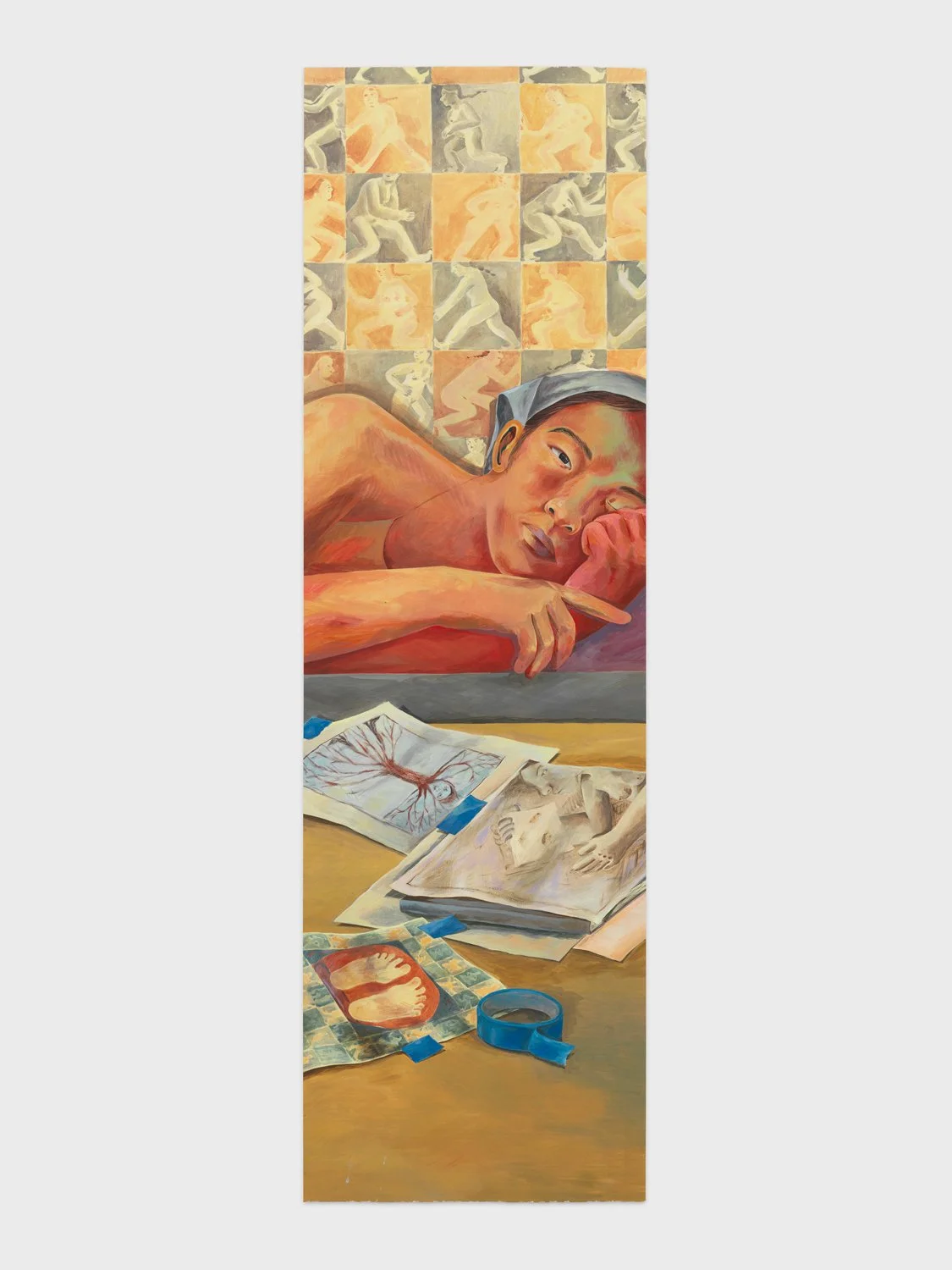

Lily Wong, The Source, 2025, acrylic on paper, 46 x 14 inches, Photo Credit: Matt Grubb

The Source is one of two paintings that not only points to outside artworks but considers that very action of pointing. Before the portrayed reclining artist, waiting to be taped to the wall with the recognizable blue artist tape, are prints of a Louise Bourgeois etching, one of Wong’s own works, and an artwork that was in the MET’s recent exhibition, Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet. This last reference is the most interesting as it inspired Wong to make the painting within the painting, visible on the wall behind the artist. There she renders her own versions of the gridded deities.

*

Time, as a symptom takes its title from a Joanna Newsom song, the last track on her 2015 album Divers. That particular album is a closed circuit, the last sound/syllable leads into the first, forever in a loop. Time is a dominant theme in Wong’s work, both in the ways that it could exist beyond our understanding, spatially and dimensionally, as well as in the weight that joy and terror place on our experience of it. In Time goes both ways (taking its title from a lyric within the show’s titular song) this is most evident, with figures repeating and stuttering across a landscape. While ominous, it reads like a less horrific counter to the visual play found in Sandro Botticelli’s The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti. The stark vertical trees seem a direct reference to that suite of images.

Lily Wong, Time goes both ways, 2025, acrylic on paper, 30.5 x 100 inches, Photo Credit: Matt Grubb

Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), The story of Nastagio degli Honesti, panel II, Date unknown, Tempera on panel, 32.2 x 54.3 inches

More references:

Two types of nostalgia are defined by Svetlana Boym in her 2001 study, “The Future of Nostalgia.” The first described is “restorative”, a type of nostalgia that “...does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition.” An easy step to fascism. The latter is “reflective” and here is where I believe Wong’s work is situated. Boym explains: “Reflective nostalgia thrives in algia, the longing itself, and delays the homecoming- wistfully, ironically, desperately. … Reflective nostalgia dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity.”

As Boym describes: “Reflective nostalgics see everywhere the imperfect mirror images of home, and try to cohabit with doubles and ghosts.” Sometimes Wong’s figures read as self-portraits of past selves and other times as variants on a type. They split and haunt each other.

Like the reflective nostalgic, Wong “desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.” Here poses recur, like the figures reaching out. (Two great examples of this are the prominent figure in Moonflower and the midground figure clothed in white undergarments in Time goes both ways which read like iterations on the same pose in different contexts.) Inside space is cavernous, outside constricted.

*

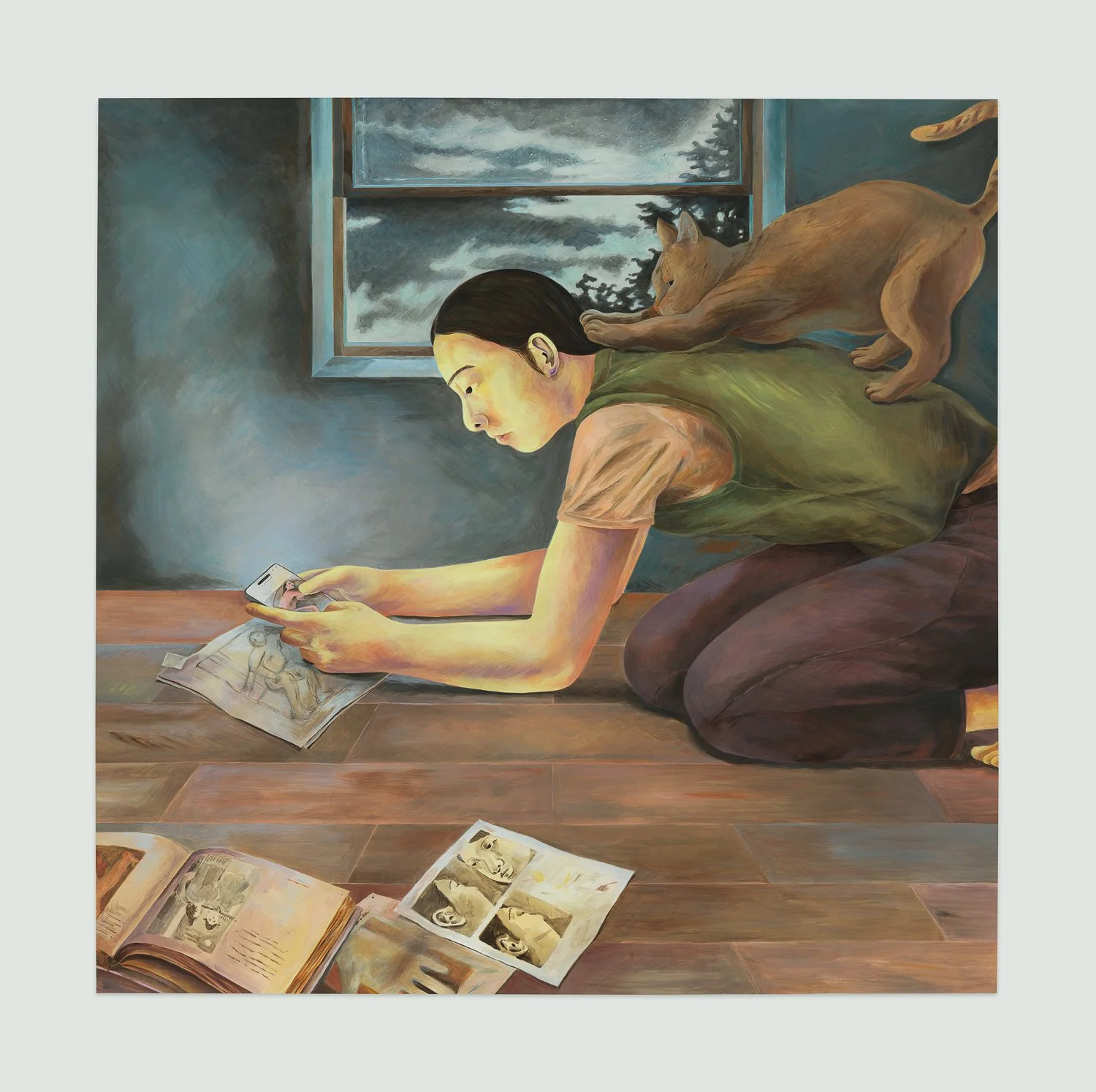

Lily Wong, Soliloquy, 2025, acrylic on paper, 46 x 46 inches, Photo Credit: Matt Grubb

In Soliloquy, the artist again arranges references, both with physical print-outs and drawings, as well as attends to the glow of her iPhone. She is crouched over in an impossible form (notice the spacial fuckery of her body in relation to the floor boards), with her cat, Louis, perched on her back. He seems to guide her, or at least anchor and ground her. Cats and dogs exist in an ambivalent space: humans change them and they change us, but neither is fully domesticated to the other. There is always a push and pull, a conflict.

Lily Wong, Wayfarer, 2025, acrylic on paper, 49.5 x 36 inches, Photo Credit: Matt Grubb

A dog nips at the figure's leg in Wayfarer, possibly attempting to stop her, either from leaving or from entering. The pose with the dog is a reference to depictions of the pedlar figure, most famously in Bosch’s panel painting from 1500, The Pedlar, and echoing across other Northern Renaissance works.

Ants that once populated Wong’s world return, like the one’s crawling at the end of her pedlar’s staff. Like the nostalgic who can never reinhabit their original home, the ants may have returned, but they don’t mean the same thing anymore. In Wong’s older work they consumed the rotting excesses of food; now they seemingly encourage the pedlar forward, even as the scrappy dog tries to prevent that movement. I think of the radically different navigational abilities of other species. There are paths that aren’t comprehensible to us. We lack their kind of proprioception.

*

A braid suggests patience, and the making of a new form from the thousands of individual strands of hair on a given head. In Moonflower, the hair is a subtle echo to the imagery of the flower stem slithering between the foreground figure’s toes. This braiding of symbols into one ambiguous image is a foundational way Wong organizes her images.

*

In front of the extremely long, horizontal Time goes both ways, Wong spoke about the scroll as having a different temporality than other works of art. It’s not meant to be seen all at once, but rather in smaller sections. The viewer can roll and search, back and forth across the document. Despite showing an entire scene, Wong allows space and time to be inconsistent across the passage.

I am again reminded of Boym’s ideas of nostalgic imagery. She states: “A cinematic image of nostalgia is a double exposure, or a superimposition of two images—of home and abroad, past and present, dream and everyday life. The moment we try to force it into a single image, it breaks the frame or burns the surface.” Wong revels in the breaking of the frame. They are not just dream spaces; They are too coherent for that. Maybe these are memory spaces, each time reconstructed by our mind. Each past altered by the present, each time.

*

Lily Wong, The Groping Hand (after Tooker), 2025, acrylic on paper, 8 x 6 inches, Photo Credit: Matt Grubb

Final Reflection:

Tooker’s The Groping Hand is reaching for something. The something isn’t legible and isn’t necessary to understand the painting. It’s about the reaching. Wong’s artist in Soliloquy is also reaching, across time and across images, trying to tap into a wavelength and transform. The rain clings to the window in pearly drops. Condensation longing to return to a large, deep body of water.

Wong points to and braids together symbols and references, with specific contexts and meanings for her, but leaves the narrative open, respecting the nature of images to mutate and transform, never remaining just one thing for long.

To return to music: Iris Dement sings “I think I’ll let the mystery be.” Kate Bush sings “See those trees / Bend in the wind / I feel they've got a lot more sense than me / You see I try to resist… If I could learn to give like a rubberband/ I’d be back on my feet.” This is the poignance of a Lily Wong painting: to allow the mystery and to bend to it.

Anthony Cudahy, Tribute to FINALITY, 2025, Oil on linen, 60 x 72 inches, Photo credit: GC Photography

Anthony Cudahy (b. 1989) is a painter living in Brooklyn, NY. His current show, ceaseless arranger, is on view at Grimm Gallery's Amsterdam location.