Tony Robbin on Andrea Pozzo

Fra Andrea Pozzo, Glorification of Saint Ignatius, Ceiling fresco in the nave of Sant’Ignazio, Rome, 1691-94

In 1685, Jesuit Brother Andrea Pozzo (1642-1709) began to paint the ceiling of the Church of St. Ignatius of Lyola in Rome to document and celebrate Ignatius’s righteous Glory when he sits with God. With his Jesuits, Ignatius brought God’s word - no, God’s plan! - to the four corners of His Earth. Indeed, Africa, Asia, Europe, and America personified are mapped to the four corners of the nave of the Jesuit flagship church in Rome, thus making of them one Christian body. Foursquare, rectilinear, upright; but just one small thing: everything in Pozzo’s design is screwy.

The nave is covered by a barrel vault, the simplest of roofs with three shallow dormer windows on each side. Think of standing under a cylinder cut through the middle lengthwise. Pozzo has virtually added another two barrel vaults on top of it; that is, he has drawn a trompe l’oeil opening in the roof through which we see a trompe l’oeil barrel vault. And in that illusionistic barrel vault there is an opening through which a second trompe l’oeil barrel vault is seen, and in that vault is yet a third and final opening where figures ascend into endless sky and heaven.

Garlands of intertwined immaterial human bodies fly through non-existent space and cast imaginary shadows on imaginary walls. A Black Queen of Africa rules her quadrant with a knot of her attendants so dense in configuration as to obscure the physical architecture. America has her own Native-American Princess in a feather headdress. Europe is a mature lady with a horse and a scepter. Pozzo does not have many, if any, references for Asia, and she is non-descript. Nevertheless, garlands of human figures abound, proliferate, bear witness, attend and ascend, all the while visually destroying the prosaic, physical architecture.

Pozzo’s 1693 book on perspective drawing for architecture, in Latin with 100 illustrations, takes a beginner step by step to show how this feat of illusion was done. Eventually, in plates 96—100 that deal directly with the nave of St Ignatius, the now accomplished designer is told to make plan, elevation, and perspective drawings on paper. And then the designer is instructed to fashion a wooden frame that makes a grid of squares with “small cords or threads to be hung up.” This frame can be lifted to the scaffolding, lit by “lamp or candle,” and used to cast perspective lines on the vault from various positions. Not discussed, only vaguely referenced as “such helps as your own industry will suggest,” is a third technique. There was a 4-foot wooden model of the nave, through which, via a hole in the floor, one could see paper drawings fitted on the inside curved roof. (I am pretty sure the wooden model still exists, and that I saw it on my first visit to the church.)

Fra Andrea Pozzo, Glorification of Saint Ignatius (Details), Ceiling fresco in the nave of Sant’Ignazio, Rome, 1691-94

We hardly know his name, but Andrea Pozzo was famous in his time. The English translation of his book was endorsed by the great architect Christopher Wren. Also, in 1707, Emperor Leopold I invited Pozzo to Vienna so that his work would be known there, and perhaps to consult on the refurbishment of Melk Abbey. The book was influential in North America. In our time, at least Pozzo’s work is famous. I have been to the Church of St. Ignatius of Lyola 10 times in two trips to Rome, in 2009 and again in 2023, and I guess that 50 visitors at a time stay for about 15 minutes each. That is 200 people an hour for 10 hours a day 300 days a year. Even if I round down the count, that makes half a million viewers every year from all over the world.

In the very last section of his book, Pozzo rebuts an “objection” that his design for the church only works from one viewpoint: There is a yellow circle in the marble inlay floor of the nave, corresponding to the hole in the floor of the wooden model. Standing on that spot viewers see the full perspective design snap into place. The criticism was that the perspective illusion should work from every vantage point, not just one spot. Because Pozzo felt compelled to rebut this complaint three times, let us parse it more fully. Christian churches were constructed to be picture books of Jesus's life and death, the creation story, tales of the prophets, and so on. The absence of these traditional elements in fresco or stained glass might well create an unease about Pozzo’s design. As recently as 1512, in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, the picture book concept was used to magnificent effect. Yet, the details of Ignatius's life, and, aside from the most general mention of it, the argument for his sainthood are not taken up. Instead of illustrating a biography, Pozzo shows what Ignatius's ascent to heaven would feel like. Additionally, from different locations on the floor of the nave, drawn columns that are continuations of real pilasters are cocked. The two ends of the vault appear to be different sizes, and in neither is there room for human figures in the upper vault, whereas the foreshortening on the sides allows for scads of figures.

Pozzo’s rebuttal articulates his intention and shows how radical his approach was. The church is one thing only: it is a ladder to heaven, the first rung of which is here on earth. Pozzo states, “Perspective is but a counterfeiting of the truth, the painter is not obliged to make it seem real from any part, but only from one determinant point only.” To emphasize the strength and solidity of his concept of the church, Pozzo is willing to have the “architecture appear with some deformity” from some locations, if at the one designated viewing point it appears “with due proportion, straight, flat or concave; when in reality it is not so.”

The single viewpoint stance makes an intellectual argument for Pozzo's understanding of the church as a ladder to heaven. There is another argument to be made, however - one that is more emotional in nature and requires an all hands-on-deck / full-court- press image of the space. The garlands of human figures in the painting energize its upward movement. The “truth” being emphasized here is that Ignatius became a saint and was brought up quickly and forcibly. The garlands of human figures do work, do need to work, from many different vantage points, and my digital photos from all around the ceiling show a convincing and powerful upward movement. And given Pozzo’s technique of moving the grid frame to many places on the scaffolding, I do not see how it would be possible to have the figures seem real from “one determinant point only.” Instead, the figures show a rush to Glory.

Andrea Pozzo was a wonderful and rigorous mathematician. More, as demonstrated in this astounding and undeniably subjective artistic tour de force, he was a sensitive and intuitive artist.

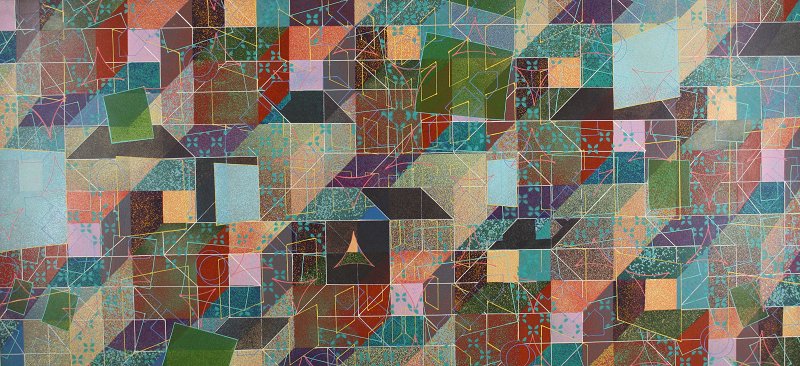

1979-8, 1979. Tony Robbin. Acrylic on canvas, 70 x 120 in. Collection of the Artist.

Tony Robbin came to New York in 1969 to be a painter. His work has a rigorous mathematical basis, and is also rich in color and pattern and lyricism.